Over time, computers have become easier to use and the internet easier to access. It used to be that people needed special training to be able to use software on a machine. Now, small children can do it. Instead of a long, noisy process of connecting through dial-up, our devices can connect to the internet (and each other) instantly, without human intervention or even awareness. Mostly this is a good thing. More intuitive design means getting more people online and bringing more access to powerful tools for self-expression and community. It would be excruciating to try and use sophisticated online tools and platforms using old-school modems and routers. One advantage, though, of older technologies is that they forced us to think about what’s under the hood of the devices we use every day. The clicking, whirring, and beeping of old-school dial-up made it obvious that digital connections don’t just magically appear—they have to be built and maintained. The problem with seamless technology is that it’s easier for tech companies to control users when the underlying operations are hidden and mysterious. Demanding change starts with understanding how technology works, who owns it, and how it’s regulated.

It’s easy to ignore the physical components that make up the internet—after all, the cables and fiber responsible for online connectivity are literally out of sight, buried underground, and stretched under the sea. Terms such. as cloud computing and wireless connection make it seem like technology is effortless and abstract, operating only in the ether. But as researchers such as Tung-Hui Hu and Nicole Starosielski have argued, there are always literal, concrete materials involved in our digital technologies. When we pull back the curtain on the internet’s infrastructure, we expose different technical layers, such as cables and wire, towers and satellites. In addition to these technical features, digital infrastructure includes the legal frameworks and rules that govern online life. From the very first packet switches of the internet, policy debates have shaped who gets to go online and how much access costs. Urban gentrification doesn’t happen spontaneously; it requires local policymakers siding with developers over longtime residents. For an online parallel, we can think about cooperation between major communication companies and government regulators. Commercialization and inequality are key features of gentrification, and they also describe a transformation in who controls access to the internet.

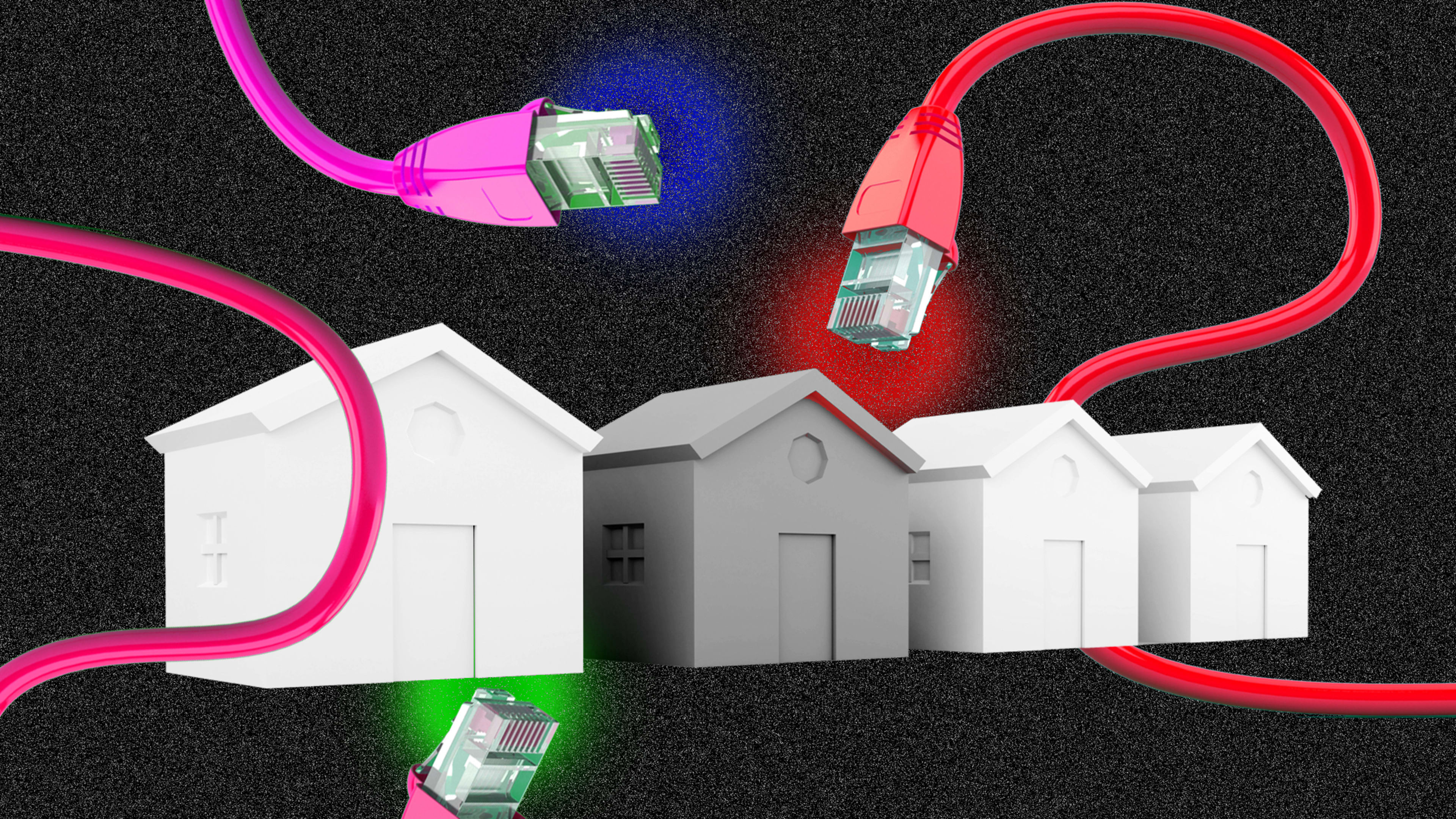

In the U.S., the infrastructure of the internet is controlled by a monopoly of companies called internet service providers (ISPs). As the gatekeepers of the fiber and cable that keeps the internet alive, ISPs decide how much power and choice users have online. How much does your monthly internet cost? How fast is it? Did it come bundled with a phone and cable TV package? Are you on a monthly contract? And maybe most important, if you wanted to switch to another provider, could you? The answers to these questions aren’t really determined by anything technical—they’re determined by the business interests and regulation of ISPs. Before people open a browser or log in to an app, their ability to access the internet is shaped and manipulated by ISPs, which is why we have to look at their history and politics.

In 2016, the United Nations declared internet access to be a basic human right, as fundamental as food, water, and freedom of movement. So you might think that governments would take the task of making sure people can get online seriously. Yet U.S. companies controlling the cost and speed of internet access have almost entirely escaped government regulation, allowing them to pursue profits rather than prioritizing access to technologies that are increasingly central for everyday working and social life. It wasn’t always this way. In its early days, the U.S. internet was tightly controlled by government agencies such as the National Science Foundation. This period of federal oversight was followed by a wave of ISP startups, which were often scrappy, ragtag, and hyper-local. The messy diversity of early ISPs was followed by a consolidation of power, driven by commercial interests rather than consumer demand. Without meaningful regulation, ISPs are free to pursue profits and ignore the needs of consumers. The lack of competition in the ISP market is bad for everyone, but it’s an extra burden on people who are poor and geographically isolated.

If we look into the history of ISPs, we can see that they’ve gentrified, with smaller, community-based ISPs getting pushed out by national conglomerates. The result is a more homogenous and much more commercial landscape. This leaves the average internet user worse off, with fewer choices and less freedom. Remembering a moment in the history of the internet when providers were more local and community-focused can help us push back on the gentrified system we have now.

Jessa Lingel is an associate professor at the Annenberg School for Communication and core faculty in the Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania. Her third book, The Gentrification of the Internet, is out next month from University of California Press.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.